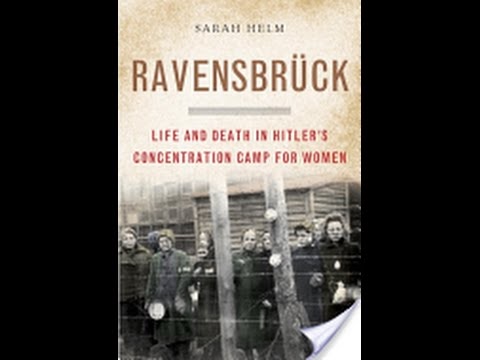

Ravensbruck — An In Depth History of Germany’s Concentration Camp for Women

Sarah Helm has written an exhaustive and exhausting history: Ravensbruck – Life and Death in Hitler’s Concentration Camp for Women. This detailed recounting of the horrific crimes committed at Ravensbruck, the only women-only concentration camp, is mind-numbing in detail. I wasn’t always able to follow the thread of all the individual women’s experiences at Ravensbruck, but Helm’s excellent writing nonetheless paints a consistently grim picture of unmitigated evil.

Ravensbruck wasn’t set up as strictly an extermination camp, although selections and mass murders were routinely conducted. In addition to executions, beatings and starvation, Ravensbruck was also the scene of grisly medical experiments, most of which were conducted on Polish prisoners. Even though many of them died, these Polish prisoners managed to communicate with the outside world about their ongoing plight. Those who survived the crippling and often fatal medical “experiments” were consistently threatened with selections designed to eradicate the evidence of what had been done to them.

Women were sent to Ravensbruck from all over Europe and for all sorts of reasons. Prisoners included Jehovah’s Witnesses, resistance workers, communists, prostitutes, intelligentsia from conquered lands and an assortment of “ordinary” German women who expressed disillusionment with the Nazi regime. There were some Jewish prisoners, but they were in the minority. There wasn’t much resistance at the camp, but the refusal of the Jehovah’s Witnesses and many of the Russian prisoners to manufacture war materiel was impressive.

Heinrich Himmler’s direct oversight of the construction and operation of Ravensbruck would be remarkable except for the fact that his mistress lived just down the road, so it was convenient for him to stop by. Himmler was keenly interested in the selection for execution process, as well as the grotesque medical experimentation. Toward the end of the war, he played an interesting game of trying to trade some prisoners with the Allies in a delusional effort to save his own skin. This was in sharp contrast to Hitler’s orders to kill all the prisoners and to prevent them from falling into allied hands.

The saga of the end of the War was a blur of last-minute executions, beatings, forced marches, starvation and dashed hopes. Unfortunately many of the Ravensbruck prisoners fell into the hands of Russian “rescuers,” who raped prisoners and non-prisoners alike. Back home, the Russian prisoners in particular were punished for the sin of having been imprisoned. Other prisoners often kept their stories to themselves.

Fortunately, some of the Ravensbruck prisoners did keep a record and some of them very much recalled what happened at the camp. Sarah Helm’s interviews with survivors are very moving. In addition to direct interviews with some of the survivors, Helm relies upon various diaries, public records and the evidence given at the war crimes trials of Ravensbruck’s administrators, doctors and guards. The matter-of-fact testimony given by some of the doctors and guards about the atrocities they committed was absolutely chilling.

This isn’t an easy read, but the women imprisoned at Ravensbruck deserve to be remembered, and this book honors them. Helm has done a magnificent job of gathering the evidence of what happened and presenting an organized history of a terrible place.